The best New Year’s resolutions are those that flow, not the ones that we force upon ourselves. Resolutions that remove obstacles to success, and those that require us to work with and for others, can actually lower the heart rate and blood pressure, and decrease anxiety and depression, while increasing our motivation to take on and persevere in difficult tasks. You might like to explore these ideas in detail in the book Emotional Success: The Power of Gratitude, Compassion, and Pride, by David DeSteno, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University.

In fiddling, these ideas suggest the benefits of playing music with others or taking a class, or having a private teacher to work with. I think folks taking our live online workshops enjoy getting together regularly, playing with the instructor (privately, with other mikes muted) and asking questions or playing for comments if they choose.

DeSteno’s ideas also suggest tell us that finding ways to remove obstacles is a better and more lasting way to learn than to try to power through those obstacles merely by “working harder”. This certainly applies to work on timing, intonation, note patterns, and sound quality, but in this article, we’re going to focus on ways to improve probably the most important aspect of fiddling — bowing. Instead of prescribing complicated movements, we’re going to describe natural ones you can visualize and apply.

The most important thing you could do for your bowing is to make sure that your mental picture of what’s going on with your bow arm actually matches what is happening. This is called “body mapping.” You can find a brief video devoted to this topic in Technique Video Group 1 (video #9), which talks about two bodymapping ideas for fiddlers — more natural left hand fingering and the right way (i.e. most efficient way) to move your bow arm.

Contrary to a fairly popular belief, the downbow is a push, not a pull. These are both natural movements, but pushing a downbow is the motion that actually gives you more control and better sound. It’s very much like drawing a line. Imagine placing your chin on a table with a large piece of paper (or literally try it!), and draw a straight line toward your right. You naturally push the pencil away from you, leading with your hand. It’s the same motion you might use if you were whittling wood with a knife, the safe way — away from you.

When you push the pencil or the knife — or the bow — away from you, your arm opens at the elbow. The elbow itself moves forward, eventually straightening into a line along your arm. When you reverse the movement and bring your arm back up to where it was so you can draw another line or carve another strip of wood, you lead with your wrist, and pull the rest of your arm along. As you pull, your elbow bends and moves toward the back or side. Meanwhile you are naturally moving the pencil, the knife, the bow, in a straight line. This is the most natural motion for bowing.

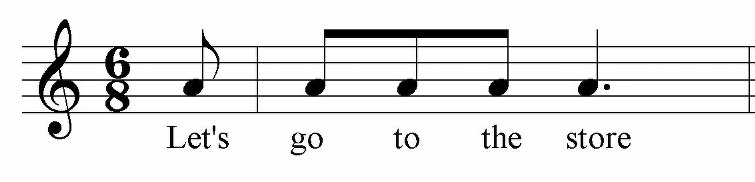

The opposite motion is also natural but not helpful to playing the fiddle. It involves trying to pull the bow downbow, and feels normal only if we think of grabbing the bow as we might grab a stick (which in a way, it is!). In this motion, we lock our elbow and pull the elbow backward, engaging the chest muscles for strength, as we would do in a tug of war, or if we were sawing a piece of wood. Bowing this way is not uncommon for beginners but it makes us sound like we are sawing, with a rough sound, because we are moving as if we’re sawing wood! Because the elbow is stiffer, the bow can’t move in a straight line (imagine drawing that line on paper with a stiff elbow), and we can only use a small portion of the bow without running into the bridge or fingerboard. We can make do with this kind of bowing if we only play short bows, as in jigs or reels, but sounds terrible for any longer use of bows, as in waltzes or other slow tunes. When the bow is not straight, it migrates toward or away from the bridge as we play, and changes the whole recipe of speed and pressure that gives a consistent sound. And if the bow is crooked when changing direction, it won’t sound smooth because the bow is forced to partially slide sideways as it starts moving the other way.

So the natural and most productive motion of the downbow is to think of it as a push, moving away from you, and led by the wrist. The natural way of playing an upbow is to think of it as a pull, led again by the wrist, which bends toward your nose and draws the upper arm behind it only as needed, saving a lot of muscular energy (the pecs are never needed for playing fiddle!).

Try practicing the downbow pushing movement by placing something (a music stand, a wall or door, or an expensive vase!) just behind your elbow as you play a downbow. If you’re using the pushing movement, your elbow will move away from the object and you won’t even touch it. If you are pulling the bow down, your elbow will knock into the object, and if it’s an expensive vase, you probably won’t do it again!

The more you think “push downbow” and “pull upbow” and “lead with the wrist”, the more you’ll discover that you can draw a smoother bow, with a better sound, and have more control. It allows you to control the bow using just your forefinger instead of your whole arm. You play better and get less tired. To explore these ideas, you might want to work with the bodymapping video mentioned above on www.fiddle-online.com, and make use of these ideas deliberately in some of the other Tech Vid Group 1 videos such as Long Bows, Double Strings, and Short Bows, as well as in Notches, Circular Bows, and Breathing Bows in Tech Vid Group 2.

I feel sorry for French fiddlers and violinists. The French word for playing a downbow is “tirer” or “pull”, and the word for playing an upbow is “pousser” or “push”. This is exactly the opposite of the most useful way to map out what the body actually needs to do when using the bow!

By reframing how you think of the movement of your bow arm to a pushed downbow and a pulled upbow, both led by the wrist, with the rest of the arm passive, you’ll remove some very common obstacles to improving your sound and bow control. Your New Year’s resolution to improve bowing will be a breeze!

©2019 Ed Pearlman

A big part of practicing is strategizing for how you plan to play through, or perform, a tune — regardless of how well you know the tune. Don’t wait for that elusive moment when you think you know it “well enough to perform,” that future time when you plan to have all the notes nailed down. You wouldn’t want to nail a bunch of wooden boards securely in place without an overall plan for where they actually fit.

A big part of practicing is strategizing for how you plan to play through, or perform, a tune — regardless of how well you know the tune. Don’t wait for that elusive moment when you think you know it “well enough to perform,” that future time when you plan to have all the notes nailed down. You wouldn’t want to nail a bunch of wooden boards securely in place without an overall plan for where they actually fit.