Scales are probably the most useful note pattern to become familiar with. Scales are simply all of the notes played one at a time up ![]() and down. On the fiddle, one note per finger plus open strings will generate a scale. All of the white keys of the piano form a scale of seven different notes before reaching the octave, the eighth note. If you start on the A (220 beats per second) just below middle C, then the octave note is also an A because it is precisely double the frequency (440 beats per second) and sounds to our ears like the same note but higher. (See article on the frequencies of nature in archives at left, from June 2015.)

and down. On the fiddle, one note per finger plus open strings will generate a scale. All of the white keys of the piano form a scale of seven different notes before reaching the octave, the eighth note. If you start on the A (220 beats per second) just below middle C, then the octave note is also an A because it is precisely double the frequency (440 beats per second) and sounds to our ears like the same note but higher. (See article on the frequencies of nature in archives at left, from June 2015.)

If you are familiar with scales you can much more easily learn by ear, as it will help you group notes as you learn a tune, so that you don’t have to think about each note individually.

For beginners, scales serve many purposes, including teaching what it means to play “up” and “down” from one note to another.

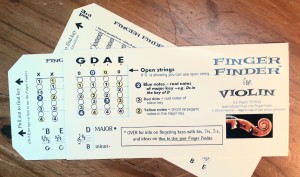

If you make use of the Finger Finder (available in Credit Store, Shar Music, or at this link), you will see scales represented visually, with numbers for each finger, and spacing in dicated for whole steps (a finger-width apart) and half-steps (fingers touching). Each key uses a different pattern of finger spacing, but as can be seen on the Finger Finder, the pattern is usually very regular except for maybe one deviation. For example, in the key of D, the 2d finger is played in the low position (touching 1st finger) on the E string; otherwise it’s high (touching 3d finger) and the other finger positions are consistent for the range of most tunes.

dicated for whole steps (a finger-width apart) and half-steps (fingers touching). Each key uses a different pattern of finger spacing, but as can be seen on the Finger Finder, the pattern is usually very regular except for maybe one deviation. For example, in the key of D, the 2d finger is played in the low position (touching 1st finger) on the E string; otherwise it’s high (touching 3d finger) and the other finger positions are consistent for the range of most tunes.

There are more scales out there than we usually think about, and they can be useful for students of all levels. For example, beginners can easily work with pentatonic scales, which limit the number of notes they have to work with while still yielding beautiful melodies. Advanced players can certainly benefit from a familiarity with pentatonic scales as they create moods from major pentatonic with a country sound, to the minor pentatonic with its bluesy feel. (See the article on the pentatonic scale, June 2015.)

The major pentatonic is generally notes 1,2,3,5,6 of the major scale, while the minor pentatonic uses the same notes starting on relative minor, resulting in notes 1,3,4,5,7 of the minor scale.

But that’s only a beginning. Classical major scales, and the melodic and harmonic minor scales are essential learning because they are so commonly used. Modal scales are common in different cultures and are sometimes best understood in this cultural context rather than as musicological theory. For example, what musicologists may call a mixolydian mode (major with flat seventh) is what Scottish musicians simple consider their major scale. Their minor scales is what theorists call the phrygian mode.

Other patterns are harder for musicologists to label. For example there is the Celtic pattern of switching regularly between one key and the key directly below, or above, which I call a double-tonic key. One of the common modes in klezmer music can be recreated by playing a melodic minor scale, but using the 5th note as the root–in other words, starting out with a half step followed by a step and a half.

Once, while working in an office at MIT many years ago, I was asked to be an experimental subject in a musical research project. They wanted to know the reactions of western musicians to hearing various modes used in music of India. I was astonished at how many combinations of scales are used in India, none of which are typical of Western major or minor patterns.

Scales used in jazz certainly expand one’s vocabulary, regardless of the instrument. Pentatonics are often used, and other scales such as whole tone scales. One adventure for ears and fingers is to play diminished scales, which alternate whole and half steps.

Maqams are decorated scale patterns used in middle Eastern and north African music. They feature tonal centers and dozens of different scale patterns expressive of different moods, usually including the fourth, fifth and octave but often working with microtonal notes in between. Microtonal notes would be considered sharp or flat by Western musicians but are part of the discipline of nonwestern music.

Even speaking of “Western” music can be misleading. Old fiddling traditions in Shetland, Cape Breton and other Western traditions make use of microtonal notes, such as the seventh being part way between the flat and sharp seventh of the piano scale. Some humourously refer to this ambiguous note as “supernatural”!

Regardless of the type of music being taught, practicing the scales up and down is a way of setting up the “keyboard” of your instrument. Fiddlers become familiar with the required finger spacing of a particular key, and then as they play music in that key, they find it much easier to play in tune.

Opening up to the possibilities of new scale patterns, and their associated arpeggios (1st, 3d, and 5th notes of the scale, or the blue+yellow+yellow notes on the Finger Finder), can stretch a musician’s vocabulary, provide valuable finger training, and help train ears to listen more intelligently to a broader range of music. Knowing the patterns makes it much easier to understand and remember blocs of notes within phrases, and to play a tune more musically.

To work on scales and note patterns, as well as view an introduction to the Finger Finder, you’ll enjoy Technique Video Group 4.

©2016 Ed Pearlman