The heartbeat of music is, you guessed it, the beat. Learners often focus on trying to play or memorize the notes of a tune and sometimes make the mistake of taking the beat for granted. It’s a mistake because the beat holds all those notes together and turns them into music.

How do you find the beat? Below, we’ll take a look at how to figure out where the beat is in a tune, whether 1) by feel or 2) on paper, with illustrations.

(Intermediate and advanced players may also find the next article thought provoking. The beat is anything but a click on a metronome. Where is it located, exactly, and how can we make the most of it? This is something we’ll take a look at.)

1. Where is the beat, by feel

It is very common that a learner may focus so much on playing the notes of a tune in sequence that they don’t think about which notes are the beat notes, and may get confused as to how to find them.

Usually people have no trouble tapping to the beat when they’re not distracted trying to play the notes. Listen to a recording of the tune and tap along as you listen and enjoy. The interactive sheet music on fiddle-online is set up to help you with this. First click on the listening track and get used to tapping along with the beat at full tempo. This could involve tapping your toe, or heel, or knee (which means the heel too!) or anything else that you feel moved to move! This can even help you when you write your own tune and need to figure out where the beats are so that not only can you play it better, but you can write it down. Take a look at the article “Stepping on the Gas” for some good ideas about tapping along to music if you have any hesitations here.

Then listen to the recording of just one phrase (using the orange audio button marked “Play A1”). Working with the first phrase in a tune is ideal so as to get the tune started on the right foot. Tap your foot to it. Remember, there should be four beats in each phrase for a jig or reel, and most other tunes, except strathspeys, which have 8. Find them! Doing this repeatedly with one phrase makes you confident that you feel the beat consistently, and as you become more confident, you can afford to pay attention to which notes are the beat notes. To do this, you may want to follow along with that one phrase by reading it.

Now try to play that one phrase while listening to the phrase audio. Notice which notes are beats and move to them as you play. Repeat that one phrase enough to be able to relax with it, and emphasize the beat notes, either by using more bow on them, or by weakening the nonbeat notes so the beats stand out.

Your bow is your beat machine, and your movement (tapping foot, knee, etc) is your physical backup system for feeling the beat. Keeping the beat in your head isn’t good enough; your head is easily overwhelmed with other tasks! Play the beat notes with a consistent bow direction to give your beats power to spare, to get comfortable with the beats, and with playing the tune. In a reel, each beat can be downbow. In a jig, the first and third beats of the phrase can be downbow, and the second and fourth beats upbow. Be consistent. Otherwise your bowing can easily work against you.

Once you feel comfortable bringing out the beat notes, you’ll find that the other notes are far easier to fit in place than they would be if you simply tried to play them all in sequence without playing them in relation to the beat.

One surefire method of feeling the beats by using appropriate lyrics. Not appropriate in the sense of socially acceptable words! If you put words to a rhythm, you can think whatever sensible, silly, bawdy words you want! Just make sure the natural way of saying the words fits the notes and beats.

2. Find the beat, on paper

Always be sure that the notes you identify as the beat notes on paper match up with feel of the beat that you tapped your foot to.

On paper, you can count on the fact that the first note of each measure is a beat note. As a general rule, play it downbow. It’s the second beat that can be a trick to see on paper.

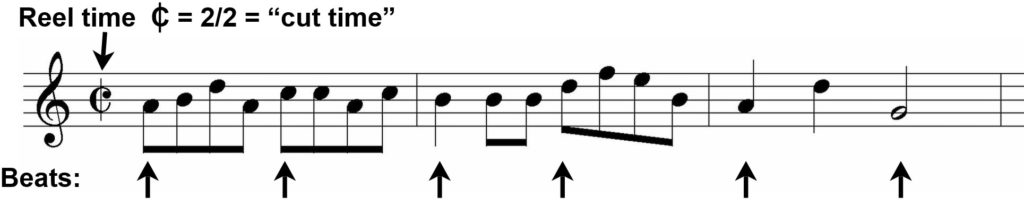

In a reel, there are two beats in a bar. Some people mistakenly write reels in 4/4 time, which confuses people into thinking there might be four beats in a bar. Just know that there are only two in a bar in a reel. There are 4 eighths in a beat. If the music is written out properly, eighth notes should be grouped into fours with beams connecting the stems. This makes it easy to see the beats, because the first note of each beamed group of four is the beat note. If a measure does not have all eighths, get used to seeing each quarter note as worth 2 eighths. A quarter + 2 eighths = a beat. Similarly, 2 quarters = a beat.

If you hate math, just keep a feel going, physically, by moving your bow and something else to support it. If you tap your foot to a reel, it will come down on each beat (a half-note per beat = 2 quarters = 4 eighths); it also comes *up*, so use that too! If a bar of reeltime is in 2/2 (cut time), then the count is 1-and-2-and, and the foot goes down-up-down-up. The more ways you can think of it, and the more games you can play coming from different angles, the more fun your brain has, and the better you’ll get the feel of it.

If you hate math, just keep a feel going, physically, by moving your bow and something else to support it. If you tap your foot to a reel, it will come down on each beat (a half-note per beat = 2 quarters = 4 eighths); it also comes *up*, so use that too! If a bar of reeltime is in 2/2 (cut time), then the count is 1-and-2-and, and the foot goes down-up-down-up. The more ways you can think of it, and the more games you can play coming from different angles, the more fun your brain has, and the better you’ll get the feel of it.

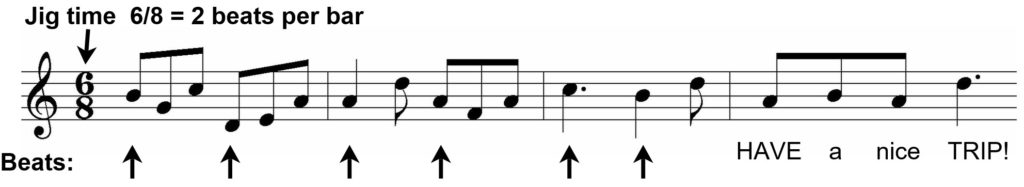

In a jig, there are also two beats in a bar, but each beat is a triplet, or 3 eighths. Usually they are written beamed together so you can count on the first of the group of 3 as being the beat note. Since a quarter = 2 eighths, a beat in jigtime can also be a quarter + an eighth, so look for that pattern as equal to a jigtime beat. A dotted quarter also equals 3 eighths, and takes up a whole beat of time. Again, the first note of the bar is the beat, and the second beat is the one to watch for — it’s the first note of a beamed triplet, or is the first note after a beamed triplet, or after a quarter + eighth. Arithmetic can help work out a tough spot but some people can’t think that way, and don’t need to. Having the feel of a jig is the same as feeling the syllables in a phrase of words, such as “HAVE a nice TRIP” where the capitalized words are the beat notes. HAVE + a + nice would represent a triplet, one beat.

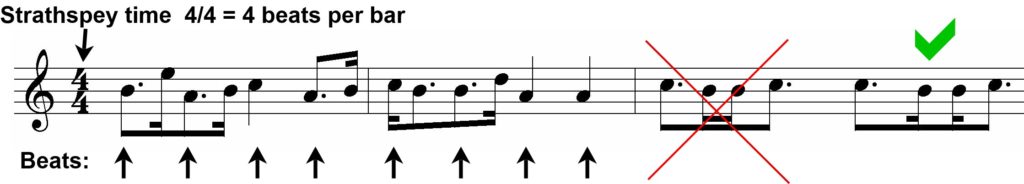

Strathspeys have four beats in a bar. Each beat is equivalent to a quarter note. Two eighths = a quarter note, but so do a dotted eight + sixteenth (same if the sixteenth comes first). Sometimes people or computers write out strathspeys weirdly, so look carefully for the four beats in the measure. Beats 1 and 3 are usually easiest to spot — beat 1 being the first note of the bar, and beat 3 usually a quarter note or the first of four beamed notes (combining eighths, dotted eighths, sixteenths). Beat 2 comes after a quarter note or a pair of eighths (or dotted eighth + sixteenth).

The problem with music software in strathspeys is that when there is a group of two beats that have dotted eighth + sixteenth, followed by sixteenth + dotted eighth, the computer will often write it by beaming the two sixteenths in the middle. Keep in mind that each pair of notes is a beat, meaning that the second sixteenth note is a beat note, and if written properly, should not be beamed with the sixteenth before it. But a lot of people let the computer do the easiest thing (software can fix this if the users make the effort but many do not know this), so watch out for this confusing notation, which makes it harder to see the beat.

The problem with music software in strathspeys is that when there is a group of two beats that have dotted eighth + sixteenth, followed by sixteenth + dotted eighth, the computer will often write it by beaming the two sixteenths in the middle. Keep in mind that each pair of notes is a beat, meaning that the second sixteenth note is a beat note, and if written properly, should not be beamed with the sixteenth before it. But a lot of people let the computer do the easiest thing (software can fix this if the users make the effort but many do not know this), so watch out for this confusing notation, which makes it harder to see the beat.

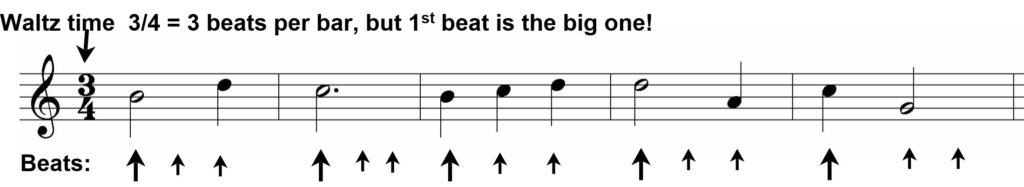

Waltzes have one strong beat in each measure, the first note. The other two quarter note beats are weaker and lead us toward the next measure.

Slow airs and marches can be written in various time signatures. The top number in the time signature will tell you how many beats there are per measure. There are exceptions in quicker tunes, such as jigs (6/8 = two beats of 3 eighths each) and some reels poorly written (they’re always felt in two beats in a bar, 2/2 time, though some allow reels to be written in 4/4).

Slow airs and marches can be written in various time signatures. The top number in the time signature will tell you how many beats there are per measure. There are exceptions in quicker tunes, such as jigs (6/8 = two beats of 3 eighths each) and some reels poorly written (they’re always felt in two beats in a bar, 2/2 time, though some allow reels to be written in 4/4).

One of the trickiest part of finding the beats by feel or on paper is when there is a dotted note that crosses over a beat. You have to feel the beat whether you change bow on it or not. For details, see the article on “The Beat Not Played”.

We’ll take a look in the next article at why the beat is not equivalent to a metronome marking, why a MIDI audio is not a human sound, and how to make the most of the pulse of a tune, to make it feel like a heartbeat.

©2020 Ed Pearlman

Very instructive! lots to digest here. I’ll be printing this one out and referring back to it as I look at the tunes. I really liked the points about computers and midi files, too. Thanks, Ed!